This about sums it up perfectly. Nobody knows better the corruption in the court rooms than the American Homeowners.

For 17 years American Homeowners have fought the banksters and their fraudulent UNREGULATED DERIVATIVES securitization scam – some successfully, some not.

BOTTOM-LINE – We’re tired of the fabricated documents, cleverly worded, but still false declarations, failure to prove standing – and especially using significantly reduced photocopies of an alleged Promissory Note, undated allonges and/or unsigned endorsements left “in blank” to further their fraud. Along with fraudulent Assignments of Mortgage, created or ordered by questionable law firms for the banks and many times back-dated, if dated at all. And let’s not forget the lower court foreclosure judges that let the Plaintiff Bank get away with it!

When the Plaintiff Trust Bank (i.e. US Bank, etc.) asserts it is a “holder” of the Note and presents an altered, shrunken (reduced) numerous generations version of a financial document that is not even a full-size copy of the original –

– and then the court that accepts that reduced multi-generational photocopied document as the original, is it any wonder why it appears that the court is committing just as much fraud as the bank?

Yes, there are statutes that cover duplicates. Under Hawaii’s sec. 626. Hawaii Rules of Evidence, Rule 1003 Admissibility of duplicates. This rule is identical with Fed. R. Evid. 1003. “A duplicate is admissible to the same extent as the original unless a genuine question is raised about the original’s authenticity or the circumstances make it unfair to admit the duplicate.”

Duplicate means to make an exact copy of something original or to be exactly the same as another item, or a genuine replacement. The real question is whether a mortgage promissory note is a mere contract or a financial debt note that, especially in securitization and rehypothecation, are treated more like currency or financial instruments that have specific monetary values?

Is It Illegal to Copy US Currency?

Who hasn’t dreamed of whipping off copies of U.S. currency and making one set of bills into hundreds of sets of bills?

But don’t get carried away and try to move this fantasy into reality. Strict laws restrict the reproduction of United States paper currency, and you’d better get them down pat before you begin.

Counterfeiting Is a Serious Crime

Counterfeiting U.S. currency is a federal crime. This shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. Manufacturing counterfeit United States currency violates Title 18, Section 471 of the U.S. Code, and you can get 15 years or more in prison if convicted. It is also a violation of that statute to alter currency to increase its value. That means you can get serious jail time if you try to change that one dollar bill into a 100-dollar bill. Source: legalbeagal.com

Even holding counterfeit United States currency can send you to jail if you are doing so with “fraudulent intent,” meaning an intention to pass the fake money off as real money. These strict rules also apply to coins. Counterfeiting any coin more valuable than a nickel carries the same penalties. Imagine Trillion$ in counterfeit mortgage Promissory Notes!

The Counterfeit Deterrence Act of 1992 upped the penalties of counterfeiting. It also allowed the Treasury Department to make new designs to foil counterfeiters, like inserting small watermarks of the portraits or using color shifting ink.

So creating fake money is a crime and altering currency and coin is also a crime. What about copying? We’re not talking about making copies of a wet-ink original – these multi-generational reduced photocopies are copies of copies printed from computers and not hard copy wet-ink originals. It’s alleged in many cases to be doubtful that the original wet-ink documents still exist. Now at Fannie Mae fraud is now being exposed and weeded out.

Copying Is Also Forbidden

Making photocopies of paper currency of the United States violates another section of the code, Title 18, Section 474 of the U.S. Code. Also forbidden under the statute: printed reproductions of checks, bonds, postage stamps, revenue stamps and securities of the United States and foreign governments. Those who violate this law can be fined up to $5,000 and/or be sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. What’s the defense here – “Your honor, the Federal Reserve made me do it”?

After 17 years, we know how securitization wiped out the pension funds. We know how intelligent foreclosure defense attorneys were threatened or actually lost their licenses. Frankly, that is a badge of honor, wear it proudly – because you had to be a damn good foreclosure defense attorney to merit their wrath and they had to be afraid of you.

The banksters made securitization so complicated and detailed, that if you weren’t a securities or federal SEC administrative law attorney – there was no way, without a lot of study and research, an average attorney or foreclosure judge would ever understand the process. If they did, there would be a lot more mortgage free homes in America, a lot less dirty banks and maybe a lot less pension deficits.

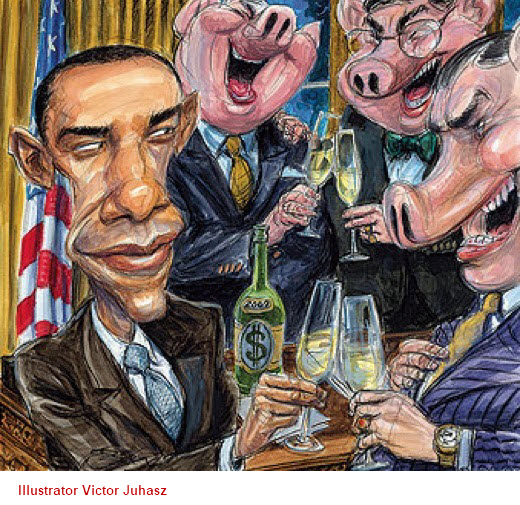

It has been rumored that judges thought ruling foreclosures in favor of the banks would save the pension funds, and that following the rule of law by ruling in favor of the homeowner would cause the complete crash of the pension funds, including their own. The pensions were gone years ago. Over $78 TRILLION in pension deficits exists worldwide (they invested in UNREGULATED DERIVATIVES – MBS, ARS, ABS and lost everything). Judges would have been better off to rule in favor of the Homeowners decades ago – rather than face exposure, corruption, and liability.

Let’s look at a current example. In 2005, the homeowner was sold an Adjustable Rate Mortgage (ARM), later determined to be Non-Traditional Mortgage (NTM). Unknown to the Homeowner the loan had been securitized – even before she signed the documents – AND THIS IS PROVABLE. As the economy went south the mortgage payment climbed.

The homeowner tried unsuccessfully NUMEROUS TIMES to get an Obama HAMP modification. Wells Fargo finally created a modification, which was actually a modified forbearance with a flat 5% interest rate (when everybody else was getting 2% and 3% full modifications with reductions in principal).

The banksters’ eyes must have burst into tears of joy when they realized they could use the already deceptive HAMP program to confiscate even more homes.

There’s a good possibility that because the date on the loan documents and the date the homeowner actually signed and notarized them were different – 3 days different, the loan had been compromised. And unknown to the homeowner, Fannie will not guarantee imperfect loan documents. These types of errors often ended up as “kick-outs” or put on a “defective loan list” – without notification made available or provided to the homeowners. Usually, the servicers just held on to the dirty paper until they could foreclose.

When foreclosure came in 2012, the Homeowner as Pro Se, defended the property and articulated the errors in the securitization as part of the argument. The alleged Assignment of Mortgage (AOM) was created 7 years after the Trust closed (12/2005). AOMs did not usually appear until a default. The Plaintiff failed to present any documents in support of its standing and foreclosure. The case was dismissed and Plaintiff had 10 days to address the defects. No such action was taken by Plaintiff. There were no Plaintiff filings until the Plaintiff filed the same exact Complaint in February, 2016, but this time with documents. This time the Homeowner had an astute foreclosure defense attorney, the Court GRANTED the Homeowner’s Motion to Dismiss WITH PREJUDICE. And the Court also DENIED Plaintiff’s Motion to Reconsider.

The foreclosure Complaint again was fatally flawed and the Plaintiff was without standing, as in the very beginning – void ab initio.

But wait! This doesn’t stop the Plaintiff Bank – SEVENTEEN (17) months later the Plaintiff finds “some soon to be off the bench” judge and files a Motion for Relief from the ORDER GRANTING the Homeowner’s Motion to Dismiss WITH PREJUDICE …

…this time with a newly added undated, unsigned and unattached allonge. Throughout the years, 2008-2016, the Homeowner continually contacted Wells Fargo (the servicer) numerous times. Wells Fargo always responded with a copy of the Note and Mortgage, but none of the servicer’s responses had any staple marks on the pristine documents, nor an allonge.

Again, the basis for the motion is in question. This motion was filed too late. The statute of limitations had expired at least the month before – if not earlier. But it appears through some slick trickery the Plaintiff made the default dates appear to be later than they actually were. It appears, the judge didn’t catch the notations in the Plaintiff’s exhibits – but the Homeowner did! The Plaintiff, or its servicer made specific instructions to Plaintiff’s attorneys and noted:

“The account with interest, advances and all other charges, is immediately due and payable as follows: The total amount due the Plaintiff on said Note through 05/10/2024 is $835,920.59; which breaks down as follows:

Principal and Interest From 07/01/2012 to 05/10/2024@ 5.000%”

Plaintiff needed the default date to be August 1, 2012 to meet the statute of limitations, but that was not to be. Good catch by the Homeowner. Additionally, Plaintiff’s servicer declarant stated, “The loan was never brought current,” “Borrower initially defaulted on the loan due to the return of the 05/01/2012 payment on 05/10/2012,” and actually provides exhibits that foreclosure had begun in 2009… making the statute of limitations way beyond the Plaintiff’s legal reach.

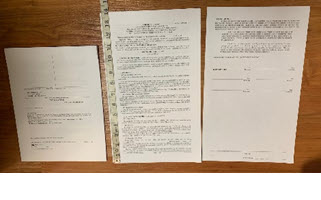

HOMEOWNER HAS ORIGINAL MORTGAGE DOCUMENTS

What makes this case even more interesting is the Homeowner has a full copy of the ORIGINAL closing documents from 2005. Twenty years later, the actual original Mortgage and Note can be inspected, but are not in the Plaintiff’s possession.

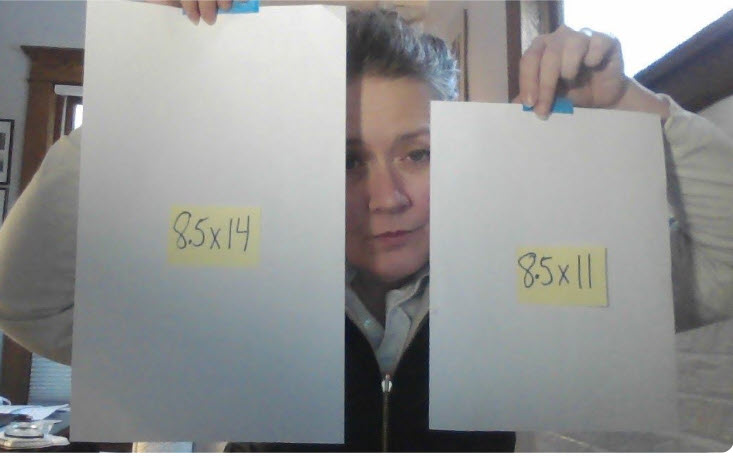

The original Note, a key document in this story, is 8.5″ x 14″ (legal size) which was standard in the securitization industry. All we’ve seen since 2008 were 8.5″ x 11″ MULTI-GENERATIONAL reduced photocopied documents…

…with no wet ink signatures in the majority of foreclosures. The Note in particular, used in Plaintiff’s 2nd Complaint was not the original size of 14” x 8.5” which was the standard size used in the securitization process. The Note was reduced numerous generations to shrink to an 8.5” x 11” sheet of paper, and in parts unreadable. Additionally, the documents were neither dated nor “certified nor sworn to in an affidavit and thus could not be verified as authentic.”

Given the inadmissibility of these materials, there exists a genuine issue as to the actual “holder” status that the Plaintiff claims. “As we pointed out in Cane City Builders v. City Bank, 50 Haw. 472, 443 P.2d 145 (1968), mere statements in affidavits do not authenticate exhibits referred to unless these exhibits are sworn to or certified.”

Plaintiff has failed to produce any supporting documentation of how it became the alleged “holder” of the Homeowner’s loan documents, precisely the Note.

In its complaints, Plaintiff inaccurately claims to be the “holder” of the note under HRS §490:3-301, “Person entitled to enforce” [PETE] an instrument means (i) the holder of the instrument. Not a copy, but the original Note. As a “holder” – holder is defined in Hawaii under HRS § 490:3-302.

a) “UCC Article 3 as a Note Title System.

UCC Article 3 functions not only as a transfer system, but also as a title system for negotiable notes, even though it is seldom conceived of as such. Article 3 is not expressly a title system. Indeed, the operative concept in Article 3 is not ownership, but enforcement rights.

b) PETE – Person Entitled to Enforce

The main rights given by UCC Article 3 are to a “person entitled to enforce” an instrument, not to an “owner.” A person entitled to enforce is either:

(1) a holder of an instrument,

(2) a nonholder in possession with rights of a holder, or

(3) a person not in possession who is entitled to enforce the

instrument pursuant to Article 3’s lost-instrument provisions.

The First of three categories of person entitled to enforce, a HOLDER requires physical possession of the instrument, which must be payable either to the bearer or to the possessor.

The Second category, a NONHOLDER, is a narrow class of parties subrogated to the rights of a holder, such as an insurer. It too requires possession of the instrument and carries with it the absolute right to require the transferor to indorse the instrument to the possessor or in blank.

The Third and final category, a person NOT IN POSSESSION seeking to enforce a lost instrument, obviously does not require current possession of the instrument. But it does require proving that the party was otherwise a person entitled to enforce before the instrument was lost—by proving possession upstream in the chain of title—as well as proving the terms of the instrument.

In the instant case, the Plaintiff’s undated and uncertified allonge indorsed in blank might fall into the 2nd category, “(2) a nonholder, that’s if Plaintiff could establish it was in timely possession of the note – and only then would it be able to establish itself as a nonholder “with rights of a holder…”. “Thus, irrespective of how a party qualifies as a person entitled to enforce, it is necessary to prove both possession and that the instrument is either bearer paper or payable to the order of the party seeking enforcement. In other words, enforcement rights are contingent upon title rights.”

[1] §490:3-302 Holder in due course. (a) Subject to subsection (c) and section 490:3-106(d), “holder in due course” means the holder of an instrument if:

(1) The instrument when issued or negotiated to the holder does not bear such apparent evidence of forgery or alteration or is not otherwise so irregular or incomplete as to call into question its authenticity; and

(2) The holder took the instrument (i) for value, (ii) in good faith, (iii) without notice that the instrument is overdue or has been dishonored or that there is an uncured default with respect to payment of another instrument issued as part of the same series, (iv) without notice that the instrument contains an unauthorized signature or has been altered, (v) without notice of any claim to the instrument described in section 490:3-306, and (vi) without notice that any party has a defense or claim in recoupment described in section 490:3-305(a).

Special thanks and credit to for the detailed definition of UCC Article 3, PETE and Holder: THE PAPER CHASE: SECURITIZATION, FORECLOSURE, AND THE UNCERTAINTY OF MORTGAGE TITLE Adam J. Levitin, Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center, pgs. 659-660

Now, with an ethical judge we’ll see if size matters in securitization, as well as sex.